ARCHIVO P.M. 2010- 2016

During a period of six years Alejandro Morales collected more than 500 photographs depicting bodies published his local newspaper P.M. in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. The time of extreme violence made Ciudad Juárez among the most violent cities in the world, marked by the large number of intentional homicides committed in its streets. The limits of what the press could publish were blurred as it was so common to find oneself in the middle of a shootout or come across an abandoned corpse. Morales removed all the corpses that he found in the photographs in the P.M. Newspaper by manually erasing them with a gum eraser.

Morales approached the newspaper from its name, understanding it as a "Post Mortem" space. When what was supposed to be in the image no longer appeared, the void that was left opened up a chance to think about what was actually happening. The softness of the eraser, the duration of the erasing process and its ritual connotations confront the immediacy and brutality of these cases. These new images intend to grant an opportunity for mourning, a more dignified form of death.

The crude way in which unidentified bodies are exhibited and photographed shows how the media is echoing the violence of the drug war and fuelling the necroaesthetic build-up which developed around it. Beyond the obvious reference to cremation of the body and to the remaining ashes, Alejandro MORALES’s erasures are a critique and an aesthetic solution at the same time. The softness of the gum, the duration of the erasing process and its ritual connotations radically confront the immediacy and brutality of these death cases. At the end of the action, the place of the body remains white, as if someone finally took the trouble to cover it with a white blanket, a gesture soothing the collective deprivation of decency and mourning.

Rona Kopeczky,Curator at Ludwig Museum in Budapest

Polvo eres, 2012 - 2013

Glass cube; 14 grams of rubber residue with which 100 bodies of the Juarez newspaper "PM" were erased.

Acquisition Award XIX Biennial of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia

Acquisition Award XIX Biennial of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia

Damnatio memoriae, 2014

EL RETRATO DE TU AUSENCIA, 2023

Awards:

2023 Shortlisted for the Paris Photo - Aperture First Photobook Award

2022 Luma Rencontres Dummy Book Award Arles - Special Mention

2022 Luma Rencontres Dummy Book Award Arles - Special Mention

In media:

Info:

Swiss bound softcover

Lenticular photographs mounted on covers

112 pages, 74 works

Offset printing

17 x 22,7 cm

First edition of 600 copies

ISBN 978-91-987606-5-1

Co-published with Kultbooks & Los Sumergidos

Designed by Fernando Gallegos ︎

May 2023

Lenticular photographs mounted on covers

112 pages, 74 works

Offset printing

17 x 22,7 cm

First edition of 600 copies

ISBN 978-91-987606-5-1

Co-published with Kultbooks & Los Sumergidos

Designed by Fernando Gallegos ︎

May 2023

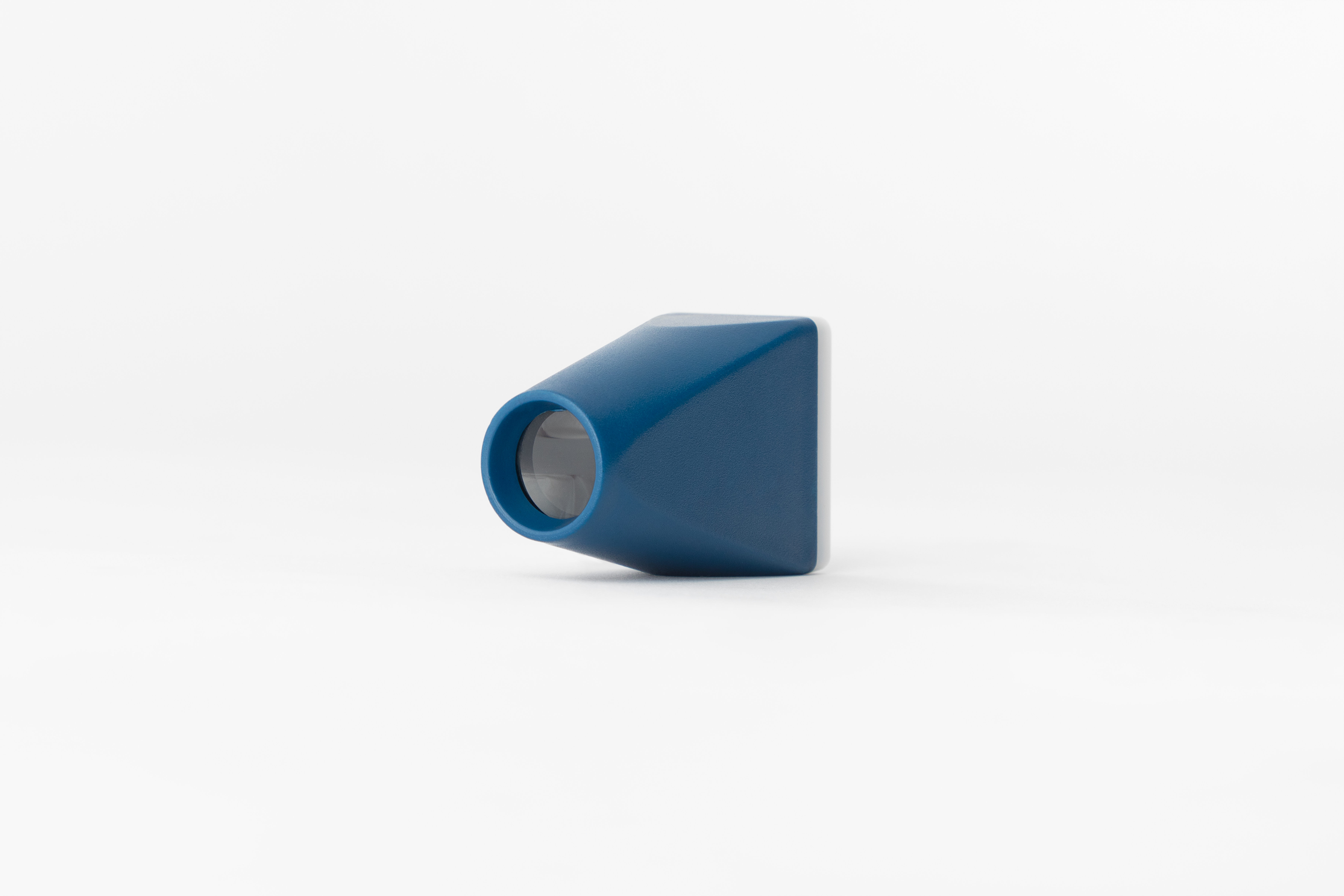

ARCHIVO JUÁREZ 2020

In 2020, unable to travel to my hometown of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, during the pandemic, I started touring the city on Google Maps. I used this tool to re-explore sites in Ciudad Juárez. With infrequent visits from the Google car and its 9-eyes camera, I often find sites that are frozen in time, many of them captured between 2008 and 2013 in a period known as the War on Drugs. I began to collect these images into a digital archive. To date, the archive has more than 500 images.

Eventually, when I was able to return home, I found myself checking through family photos and found an old keychain photo viewer—a small plastic object one could hold up against light to view a 35mm slide. Inside the viewfinder it was a picture of my parents and my brother in the circus, I was not born yet.

I think of this project as a (strangely) familiar album of my city, one that has been represented endless times with violent images. Instead of blowing these images up, I started converting them into an analog image as a 35 mm negative and inserted it into a pocket-size viewfinder, showing images that we rarely associate with the city, which was known as one of the most violent in the world. What we see in Street View becomes an intimate and personal history.

I was born in Juarez, and I chose to revisit familiar neighborhoods, avenues, and streets, showing daily life in the city through the lenses of Google’s equipment, using its own language and therefore its glitches and its artificial intelligence, an A.I. that automatically erases faces, or anything that looks like one. While the project does not focus on violence, it is impossible to navigate the city without police, military, a gunman, or abandoned houses being part of the city landscape.

Exhibitions:

- Todos me amarán, Arte de México Hoy. Fundación Casa de México en España, Madrid, Spain.

-

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as it’s kept. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

-

Archivo Juárez, Getxophoto,Festival Internacional de Imagen. Getxo, Basque Country.

- Revisión 2022. Fotógrafos de Nuevo León. Fototeca del Centro de las Artes, CONARTE, MX.

BRUJA 2014

I attempted to cross tumbleweeds stuck on the border fence between Juarez, Chihuahua, and El Paso, Texas, preventing their natural course in the Chihuahua/Texas desert.

The tumbleweeds are also known as Brujas (witches) because sometimes they catch on fire, and you can see them rolling in the desert. An impossible task, this action shows the scope of migration policies and barriers and their effects on nature.

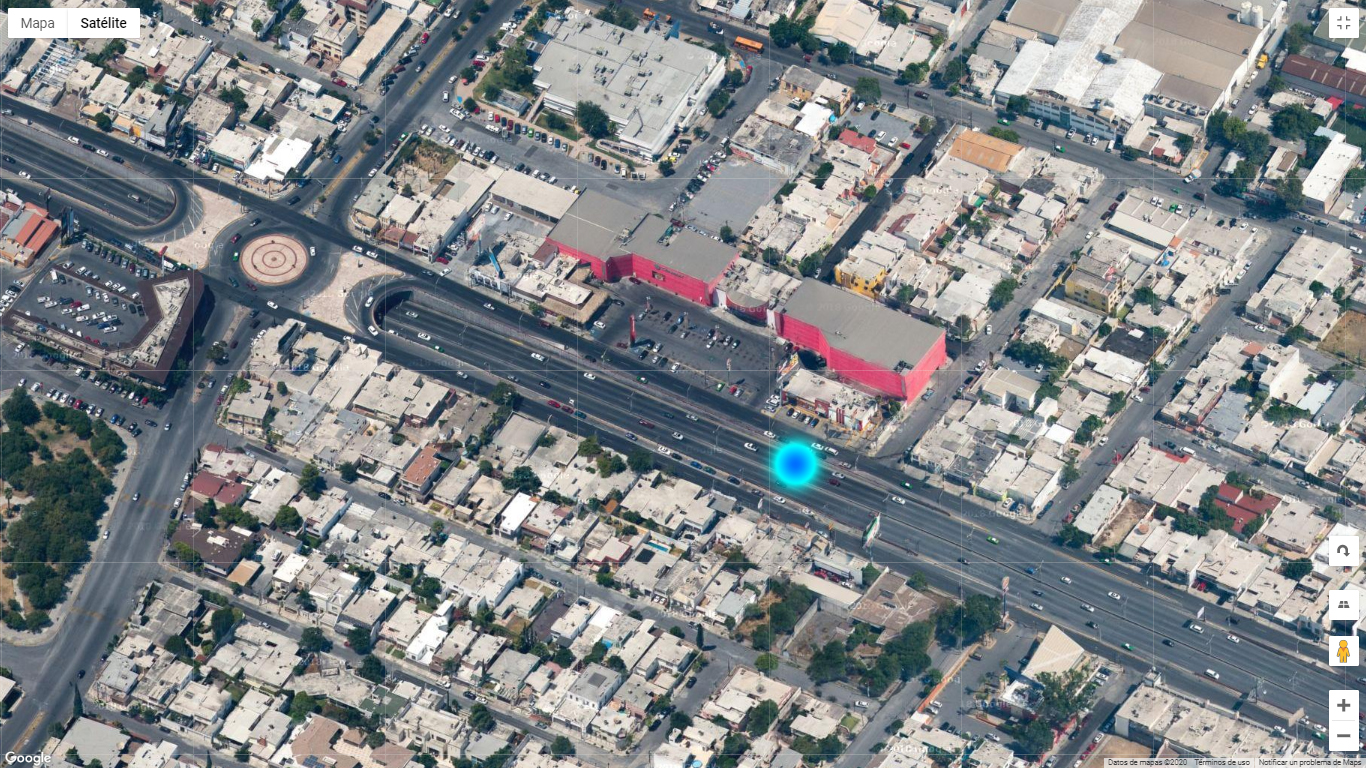

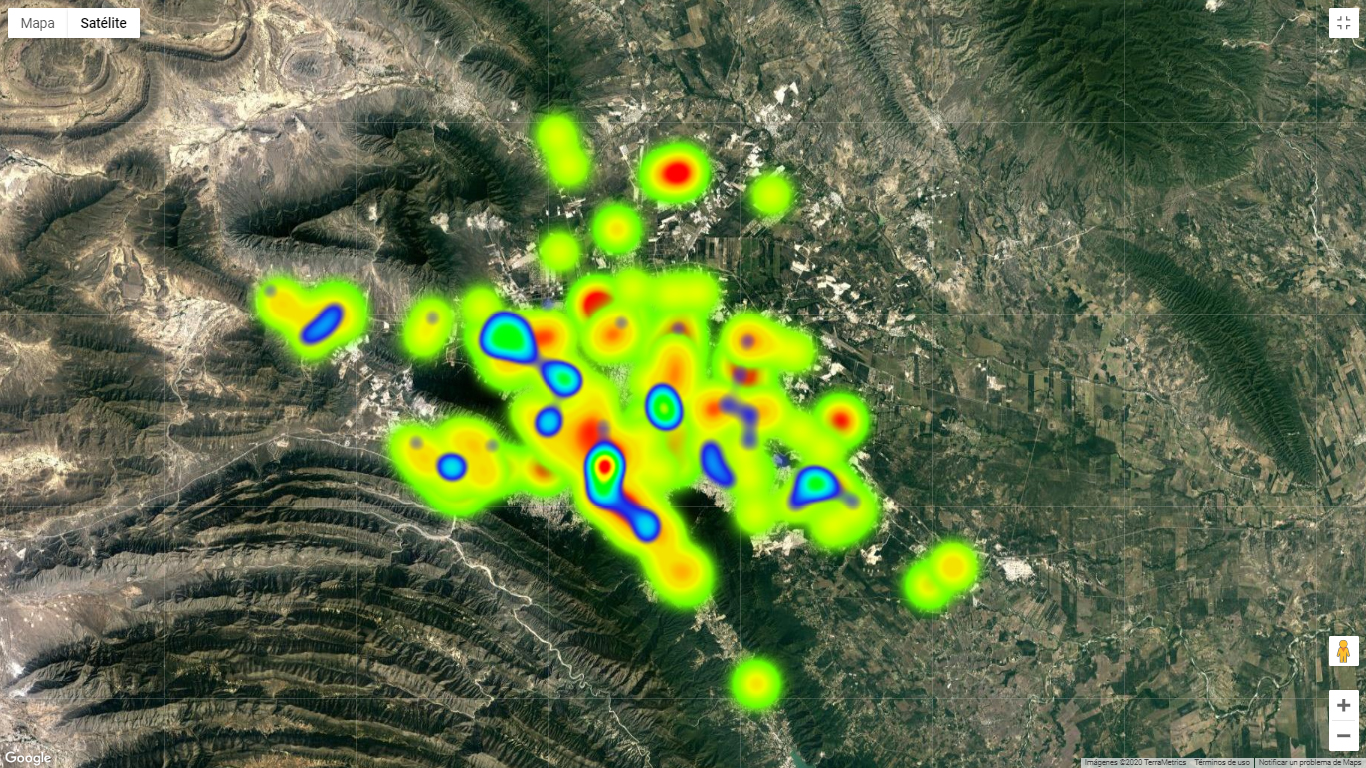

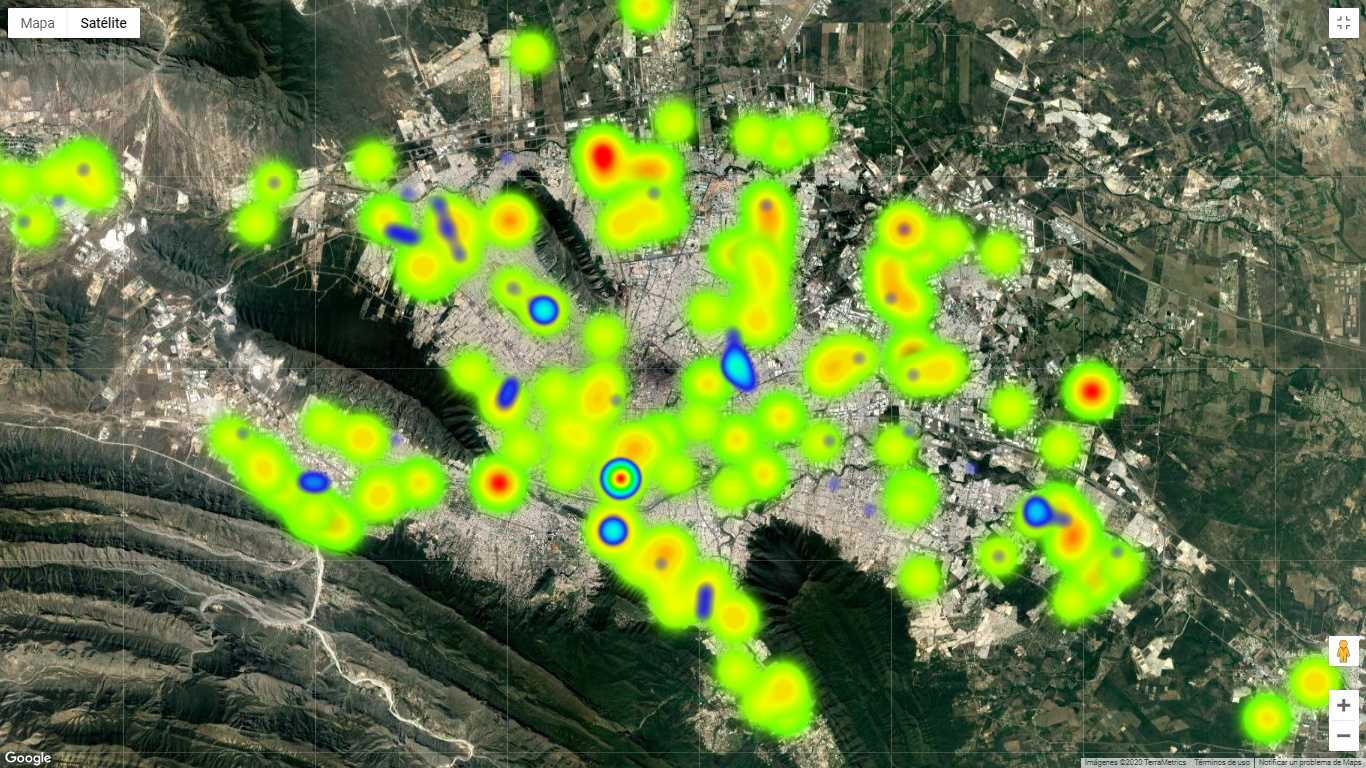

MAPA DEL DELITO 2020

The Attorney General's Office of the State of Nuevo León makes a geolocation tool available to the general public through Google Maps, registering the crimes of carjacking, home invasion, personal and business theft in real time through the Crime Map. Through this page and manipulating the Zoom In, Zoom Out options and the combination of the available filters, they were generated photographs printed with compositions of color and shape that are distributed on satellite images of the territory. The figures abstract and colorful contradict his origin.

RANCHO IZAGUIRRE 2025

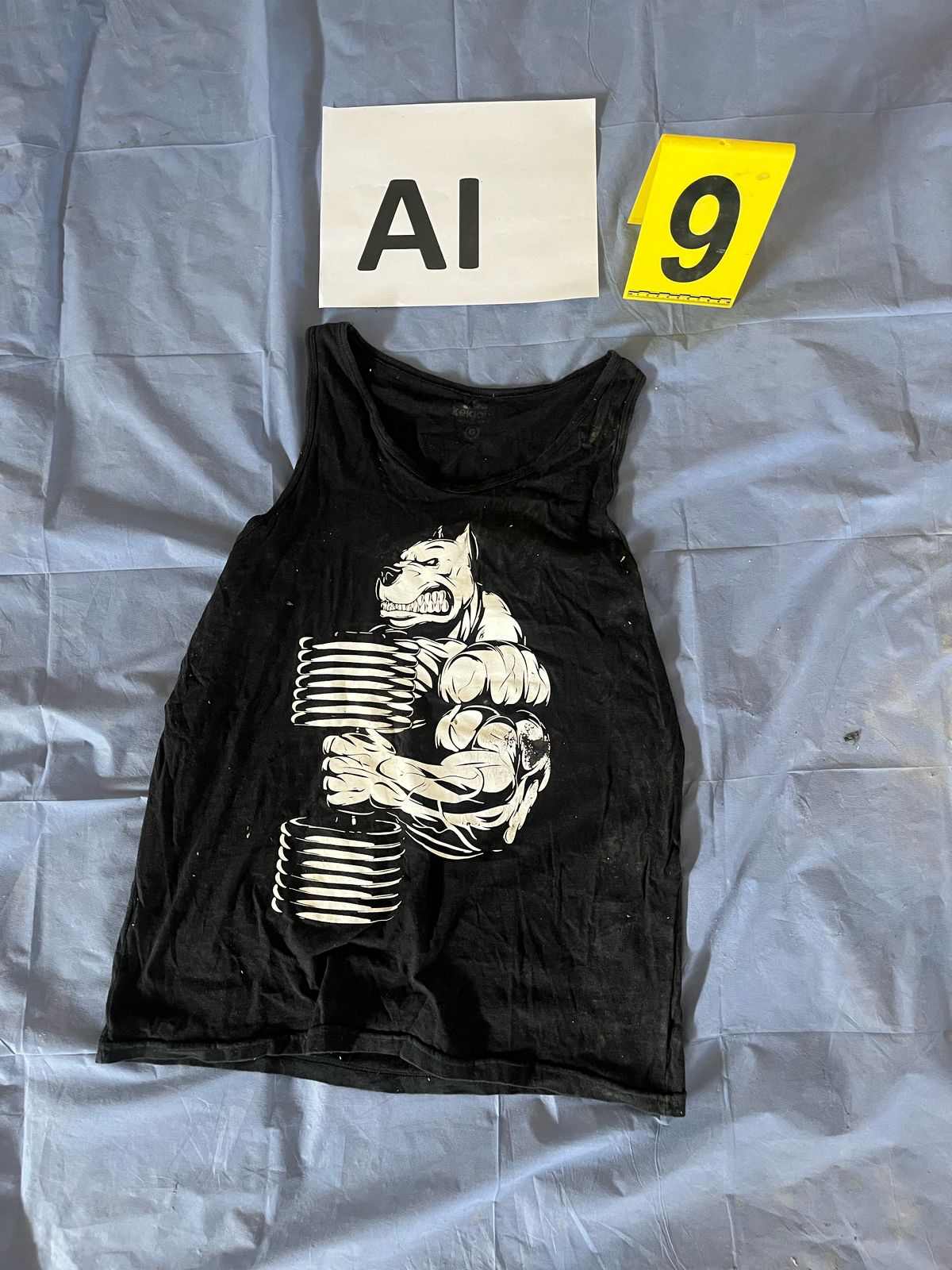

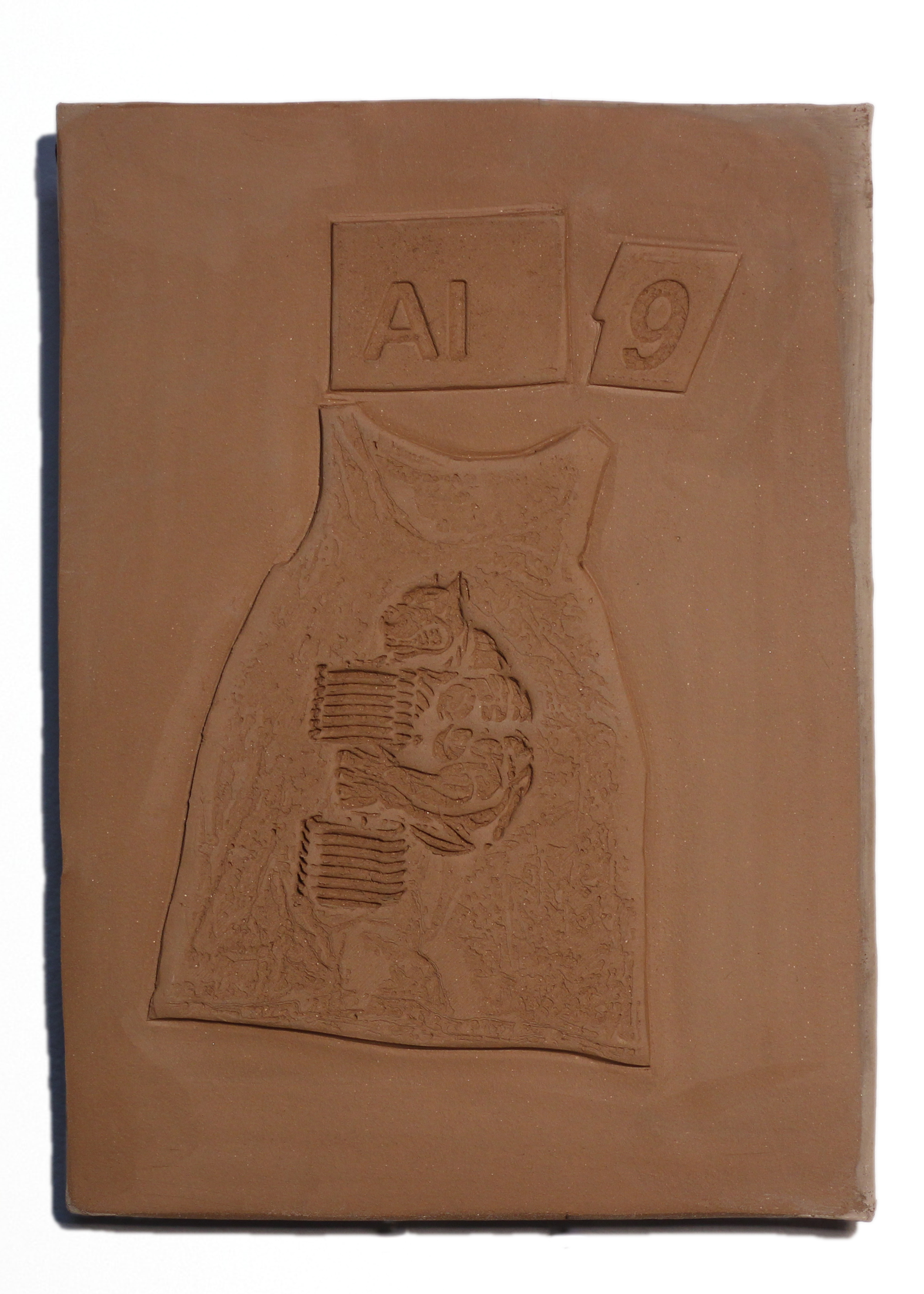

In September 2024, authorities in Teuchitlán, Jalisco—about an hour from Guadalajara—secured a property known as Rancho Izaguirre. Months later, in March 2025, a group of volunteer searchers entered the site and found something devastating: human remains, hundreds of personal belongings, and three ovens that, according to their observations, had been used to burn bodies and possessions.

The discovery shocked the region and exposed deep contradictions in how Mexico handles mass disappearances. While independent forensic experts and journalists reported layers of ash, fuel residues, and burned bone fragments, the federal prosecutor later stated that there was no conclusive proof that the site functioned as a cremation facility. These conflicting reports reflect the wider crisis of truth and recognition in the country—where even the material evidence of violence becomes contested.

Since then, the Jalisco Prosecutor’s Office has published an online catalog featuring 1,617 objects recovered from the property: clothes, shoes, belts, and backpacks that families can browse in the hope of recognizing something. Most of these items are heartbreakingly ordinary—the kind of things any of us could own. Recognition becomes a cruel exercise: deciding whether a simple t-shirt, a pair of jeans, or a school backpack might have belonged to your loved one.

For this work, I created one ceramic piece for each “group” of objects in the catalog. The forensic teams organized the evidence alphabetically—A to Z, then AA, AB, AC, and so on—because there were too many to fit into a single series. The clay is shaped, marked, and then fired in a kiln. For me, that process connects directly to the site’s ovens: the same fire that was meant to erase becomes a way to make something endure.

This installation transforms a cold digital inventory into a physical presence. It’s about facing the scale of violence while holding on to memory in a material, human way